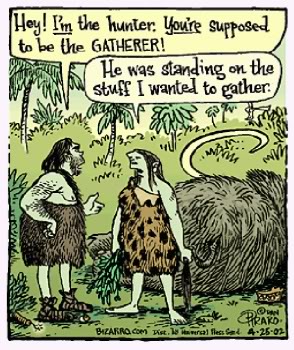

Credit: Dan Piraro

Credit: Dan Piraro In the article “The problem of maturity in hip hop,” Lewis Gordon argues that the essence of maturity is a tragic consciousness. The difference between a child and an adult, says Gordon, is that a child thinks that there are no limits to what they do, that their every action has a simple cause and effect, and that their innocence always matters. An adult, however, understands that “that things are not always neat, that making decisions is complicated, and that people often make mistakes.”

At the institutional or social level, a tragic consciousness makes us aware that in instances of institutional power, the privileged and powerful must suffer, or be sacrificed, for justice to be restored. In tragedy, the innocence of the powerful who suffer – be it Oedipus, Antigone or Lwanda Magere – is largely irrelevant.

French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre came to this tragic realization in his fight against France’s exploitation of people in the colonies. That is why he accused the early 20th century French bourgeoisie, who tried to distance themselves from the actions of the French government in Africa, of bad faith. No matter what the French thought, they were implicated in their country’s actions. As Sartre put in his preface to Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, between any two French men lies a dead African.

By Gordon’s definition of maturity, Sartre was an adult man.

*

Gordon articulates a view of maturity that we Kenyans practice all the time. Children often complain of their parents’ favoritism towards their younger siblings because parents know that the understanding of three year old is different from that of a six year old, rendering the younger sibling in need of a different kind of attention than the older one. When we tell adolescents to stop being childish, we’re essentially telling them to understand that there are other people, other forces in the world that they must take into account, and their actions have implications and consequences. Similarly, our African initiation rituals enforce a sense of maturity among adolescents. The reason we tell men to endure the pain of circumcision is to teach them that such is life; that as adults, men will have to make personally painful but socially beneficial decisions, that innocence is sometimes less important than responsibility, because men live in a world with other members of the cosmic universe.

But the reason we fight against FGM is because it is a ritual that takes pain too far and mutilates the woman’s body and soul. Rather than teach her that life is complicated, FGM paralyses the humanity of the woman, making her unable to survive or function when faced with other life complexities such as childbirth, work, intellectual maturity and citizenship. At the communal level, ostracizing women means alienating half the population.

At the national level, our failure to understand the tragic position of the colonial settler left us with a curse that Kenya is yet to break. After the Mau Mau liberation struggle, the colonial settlers demanded that Kenyatta I treat the settlers “equally.” So rather than take back the land the settlers had taken, Kenyatta I instituted “willing buyer, willing settler” scheme that was supposed to equalize the land market, but ended up leaving the Mau Mau in the very same landless situation that had compelled them to take arms against colonialism in the first place. And Kenya took a loan to pay settlers at the inflated land rates, and we'are still paying back that loan. And killing each other at different election years over land.

Such are the lessons of the failure of maturity, and of our education system to teach people to think of the larger social dramas and not just the identity of the actors. And it also explains why the Kenyan mainstream conversation on gender remains immature. Over the last few years, despite the fact that the number of Kenyan women remains negligible in decision-making and property ownership, advocates for the boy child continue to lament that the culprit of the neglect of Kenyan boys has been advocates of the Kenyan girl child.

I know: it doesn’t make sense. But the conviction with which several Kenyans, from the uneducated to the scholar, repeat this fallacy, is simply outstanding.

Such persistence is a sign of immaturity that comes from centuries of patriarchal privilege that got a boost from colonialism. It signals the failure of Kenyans to acquire the tragic realization that in patriarchy, men’s innocence is largely irrelevant. By virtue of being favored by patriarchal religion, education and other social institutions that take men’s experience and view as the default worldview, tragedy denies men the right to claim discrimination at the hands of the the victims of patriarchy – women that is – who are fighting for a more human social system. In other words, the sign of maturity in a man is the realization that ultimately, the fight for the girl child is not for him, and can never be for him. To demand that advocates for the girl child include the boy child in their advocacy is to lack a tragic-consciousness. It is to be immature.

Like Sartre, Kenyans must learn to identify and fight the battles specific to boys on those battles’ own terms, rather than react against women fighting their own. Complaints of neglect from girl child advocates are as narrow-minded as those from an older sibling wondering why he needs to eat vegetables when his toddler sibling is still suckling, unable to realize that the parent cares for each of the children according to each child’s needs. We need to build a Kenyan nation whose laws, institutions and consciousness cater for each group of citizens, according to the specific group’s needs. Kenyan intellectuals and the mainstream media need to develop complex thinking about gender, not adopt a simplistic and blanket logic full of fallacies, where everything done for the girl must also be done for the boy. Simplistically put, we need to approach the complex, multifaceted issue of gender like adults.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed