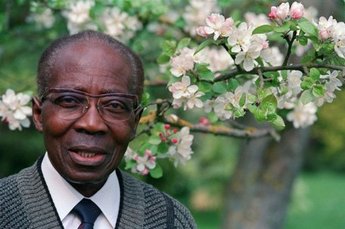

Senghor (Source: Derniere Minute, Senegal).

Senghor (Source: Derniere Minute, Senegal). As part of the Negritude movement, this formula was meant to assert Africans’ mark on the world, a mark that colonial historiography had tried to obliterate by calling Africans uncivilized or absent from history. But as we now know from the many responses to Senghor’s theory, this formula was very problematic. It basically accepted the argument about Africans being irrational, but explained our apparent irrationality and lack of civilization as innate because we were emotional. We Africans feel, the explanation went; we don’t think.

To this day, every academic who studies history, philosophy and literature of the continent must go through a course on Negritude, which includes a ceremonial tongue –lashing at Senghor for being too French (he spoke French better than many of the French), for setting up African women on an impossible pedestal, and for accepting myths about Africans. Fair enough.

But looking at reactions to the World Cup win by Germany on Sunday, it is evident that the world still divides the human race into the rational and irrational, reserving the former for Europeans (specifically Germans), and the latter for South Americans. This time Africans are not included because the conduct of the African teams, specifically Cameroon and Ghana that were burdened with in-fighting and indiscipline, seems to put us outside the realm of discussion. We were worse than irrational; we were incoherent.

And we African fans perpetuate these myths at every World Cup. We cheer our continent’s teams with no conviction that we actually stand a chance of reaching the semi-finals, let alone of lifting the trophy, as we wait for African teams to be eliminated so that we shift to cheering the South Americans, whom we think stand a chance. We also look for hot button names like Neymar and Messi that we can keep mentioning. It’s easier to remember larger-than-life individuals than pay attention to details about team-work and unity. Rooting for the Germans, the French, or the Dutch is not an option, I guess because of our historical baggage with Europe, which is understandable. Never mind that these teams often have people of African descent, or even born in Africa, like the 1998 French World Cup Champions.

So when the Germans thrashed Brazil 7-1, the narrative of the rational and irrational was shaken, but not uprooted. Journalists in our dailies called the German team a “machine,” and used words and metaphors to depict a cold, unemotional and mathematically calculated win over a team known to play with “flair.” Come the finals, most of the world knew that Germany was the better team, but many Kenyans still rationalized their support of Argentina as the fact that the country is excluded from the “first world” like us, that Argentina has Messi, and that it plays with flair and emotion, and football is supposed to be an emotional sport.

The problem with this narrative is that it misses the essence of humanity, that we are simultaneously rational and emotional, spiritual and rhythmic, and every beautiful aspect that makes us human.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed