Le chemin de l'exil (The path to exile) by Congolese artist Cheri Cherin, 2004

Le chemin de l'exil (The path to exile) by Congolese artist Cheri Cherin, 2004 In this letter, I’m going to talk about how capitalist business is the prime beneficiary of the terrible state of the arts in Kenya.

Le chemin de l'exil (The path to exile) by Congolese artist Cheri Cherin, 2004 Le chemin de l'exil (The path to exile) by Congolese artist Cheri Cherin, 2004 It’s me again. In my last letter, I talked about how our education system destroys the arts by corrupting the meaning of education, work and the arts. And I said that these lies which are perpetuated in the name of education come from the unholy and abusive marriage between education and business (I have said elsewhere that this marriage should be immediately annulled). In this letter, I’m going to talk about how capitalist business is the prime beneficiary of the terrible state of the arts in Kenya.

0 Comments

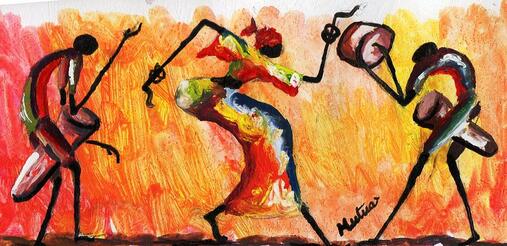

Art Class, by William H. Johnson, at the Smithsonian, USA Art Class, by William H. Johnson, at the Smithsonian, USA Dear Kenyan artist In my previous letter, I talked about how the arts are a divine calling. The arts make us human, because the arts provide a space for us to be social and individual at the same time. With the arts, we accept what we can’t change and change what we can, while producing something creative and sometimes new. Let me give an example of what I mean. The rituals we perform when someone we love dies help us accept death as something we all must face. However, we cannot raise our hands and say death is inevitable, because if we do, we would not have reason to live our lives to the fullest. So the arts is where we deal with that contradiction. When Amos and Josh sang “Tutaonana baadaye,” they are singing “we accept your going is inevitable, but until we join you, we must still live our best lives, love with all our hearts.” And from this deep truth, Amos and Josh and King Kaka produced a beautiful song. That’s what the arts are – beauty that carries deep truth.  Akamba Dance by William Mutua Akamba Dance by William Mutua Dear Kenyan artist This is an open letter to all of us Kenyans who do not behave like Jonah who tried to evade his divine calling to preach God’s message in Nineveh. I know that I speak for many when I say that in Kenya, the arts sector is abusive. To enter it is not for the faint hearted, and few of us come out of it intact. Many of us, myself included, have experienced of depression or panic attacks. A number of us are shot in the neck or are victims of rape. And each time the violence happens, the public winks and says we should have seen it coming. They say that we brought it on ourselves by talking, dressing or thinking differently.  "Morning graziers," by Ronnie Ogwang. Photo by Shine Tani. "Morning graziers," by Ronnie Ogwang. Photo by Shine Tani.

Theater scholar Gĩchingiri Ndĩgĩrĩgĩ writes that in 1991, at the height of the clamour for multi-partyism, the government denied a license for the staging of a play “Drumbeats of Kirinyaga,” by Oby Obyerodhiambo.

The reason given was that the play portrayed an ethnically diverse and politically cohesive Kenya, which contradicted the president’s argument at the time that Kenya was too ethnically divided for multi-partyism. While President Moi was claiming to care for Kenyans who are too tribal, his government was ironically also suppressing any public display of Kenyans transcending their tribal identities. The government needed to encourage tribalism among Kenyans in order to give itself something to cure.  Source: The Boston Review Source: The Boston Review In 2009, Dambisa Moyo, a Zambian economist, caught the world by storm with her book Dead Aid, in which she argued that foreign aid does not deliver the development that it promises to Africa. Dr. Moyo is as mainstream as they come: she was educated at Harvard and Oxford, she speaks impeccable English, does most of her speaking circuit in the West. And her idea was not new. Africans have questioned foreign aid since independence, because of the strings attached to foreign aid. They have said that our economic dependence on the same people who enslaved and colonized us essentially meant we were not truly independent. What was different about Dambisa Moyo?  Source: sevenly.com Source: sevenly.com ,This past week, I was a panelist in a session that reminded me of a famous discussion that took place at the African Studies Association conference in 1995. I first heard of that conference from Mshai Mwangola, when she was introducing Prof Micere Mugo who was giving a keynote address at the University of Nairobi a few years ago. The discussion took place in November 1995, in a panel convened at the African Studies Association conference to respond to an article by Phillip Curtin, the eminent African history scholar, published in March in the academic magazine Chronicle of Higher Education. In the piece entitled "Ghettoizing African History," Curtin offered anecdotes of hiring practices that, in his view, were reducing African history scholarship to a “ghetto,” because American universities were reserving African history positions for faculty on the basis of their black skin, rather than on their competence.  Harriet Powers Bible Quilt. Source: The Smithsonian Harriet Powers Bible Quilt. Source: The Smithsonian Over the last few weeks, I have come to understand at least three narratives which some Kenyans use to wish away the contradictions of the Kenyan state. No matter how much such Kenyans are presented with evidence of changing times or with history that gives a different perspective, they will repeat these narratives louder to drown out the other voices. Behind all these narratives lies an effort to wish away the fragmentation of the people by the Kenyan state. But, more than that, these narratives are protected by the curriculum of the public schools which does not allow the teaching of arts, and particularly the teaching of history. Kenyans are thus denied the opportunity to develop their intellectual capacity to understand not just the limitations the Kenya state, but to understand the reality of the world in the 21st century. The narratives are: |

|