A few weeks into the protests that were sparked off by the Kenya government’s belligerent persistence in passing the Finance Bill, the government spokesman, Isaac Maura, held a presser in which he offered a strange apology to Kenyans. As he announced the president’s concessions to the protestors’ demands, he talked off the script and said: “On behalf of any public official who has been seen to be opulent, proud and arrogant, I wish to issue an unreserved apology to the people of Kenya. Going forward, public officials shall demonstrate responsibility and humility, as has been instructed by our appointing authority, our president.” He repeated, “I wish to offer an unreserved apology for that opulence and arrogance of matters that could be seen to be contemptuous of the sufferings of Kenyans.”

0 Comments

A market scene painted by Ugandan painter Hoods Jjuuko. A market scene painted by Ugandan painter Hoods Jjuuko.

I wanted to wait to write about Mwalimu Micere Mugo until the rites to honor her life were completed, because I wanted to respect those who knew her intimately. I didn't. I met Mwalimu only three times, once at Riara University, another time at University of Nairobi, the other time at the memorial of her daughter Njeri Kui. All were public events, so I'm almost sure she barely remembered shaking my hand, or me re-introducing myself or being re-introduced to her, especially when she was grieving her daughter.

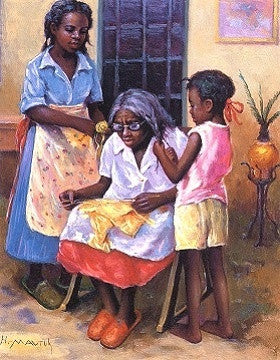

So I do not grieve Micere Mugo as I would a close friend. Instead, I grieve her as my mile stone. Since the day I heard her speak in person, almost ten years ago at the University of Nairobi, she has been my intellectual north star. My guiding light. When I heard her weave her ideas with her poetry, and engage the audience in her performance, I knew that that is what I wanted to be; not necessarily an oraturist like her, but an intellectual who weaves humanity into her thought, relations and politics. And then being in literature, many of my colleagues were taught by her and were friends with her. So her influence on me is probably what she aspired for, which is to influence humanity through humanity.  Three Generations, painting by Hulis Mavruk Three Generations, painting by Hulis Mavruk

Many with a decent knowledge of neo-colonialism and global racism may have been shocked at the amount of Western decadence, from Anglo-American political stars and billionaires, that has flowed into Kenya in the first few months of President Ruto’s tenure.

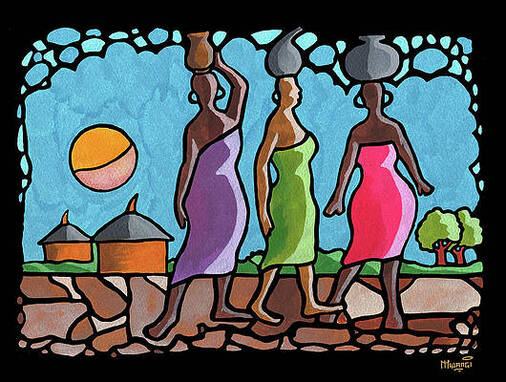

Without a public discussion, the ban on GMOs was lifted by decree, with a fairly racist caveat that since we Kenyans are dying of famine anyway, we need GMO foods to fill the gap. Weeks later, this dystopian logic would be openly articulated by the Trade CS who, in a poor attempt at sarcasm, said in the midst of the morbid laughs of his elite audience: “By just being in this country, you are a candidate for death. And because there are so many things competing to kill you, there is nothing wrong with adding GMOs to that list."  "African catwalk," painting by Anthony Mwangi "African catwalk," painting by Anthony Mwangi

The last few months, and even the last five years, have been a journey of abuse from the political class. Uhuru Kenyatta, especially, kicked tantrums when he did not get his way, undermined the constitution using the armed forces, unleashed toxicity into the public conversation through public relations and the media, and sealed this manipulation with an intellectually stunting new education system. It has been a five-year war on the Kenyan soul.

But Kenyans have courageously fought back. The vibrant public sphere and citizen mobilization have stopped insidious policies like Huduma Namba and BBI. Landmarks in jurisprudence have been achieved. Amidst these victories, both Uhuru and the civil service bureaucrats have struggled to hide their irritation that Kenyans have used the constitution to demand proper governance.

As I watched a few clips of the Sonko Leaks, until I could no longer stand the toxicity, I wondered to myself: why on earth do people who are already rich and well educated demand bribes, when they definitely do not need the money?

The answer I came up with was this: they do it to humiliate. There is something about them that is so hollow, that they can only feel themselves by degrading others. The point of bribes is not to earn money, but to assert power by shrinking the human dignity of others.  "Meeting under the tree" by John Ndambo "Meeting under the tree" by John Ndambo

I grew up knowing that in Kenya, it was a crime to ask questions. I was bullied in primary school for my “big mouth.” In high school I was blasted for being like my father. At church I was reprimanded repeatedly for literal blasphemy, and I still am, any time I cried out “my God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

But even as I endured this humiliation, I always knew that the one place to ask questions in Kenya was the university. Yes, I knew that Micere Mugo, ES Atieno Odhiambo, Willy Mutunga, Ngugi wa Thiong’o and many others had suffered for exercising intellectual freedom. I knew that university students had been jailed and killed for demanding democracy and authentic education. I knew that police hated students and would beat us at any chance.  "It takes an entire village to raise a child," painting by George E Miller "It takes an entire village to raise a child," painting by George E Miller Very rarely do I speak publicly about my family and my relationship with my father, because I am an intensely jealous daughter. I refuse to share my relationship with my father with the public, because our lives were public already, both due to my father’s career as a church minister but also due to the political positions he took. When I was young, I often used to be asked what it felt like to be a pastor’s child. I would reply that I don’t know, because I only know him as “Dad.” I learned to do that from my mother who constantly refused the label “pastor’s wife.” She argued that that label was used to the disregard the clergy as workers who needed to be treated decently because they too had families. Unlike the posperity gospel churches, the PCEA sometimes treats clergy like TSC treats teachers, posting them at the drop of a hat with little consideration about what the relocation means for their families. So I learned from my mother to protect my relationship with my father. |

|