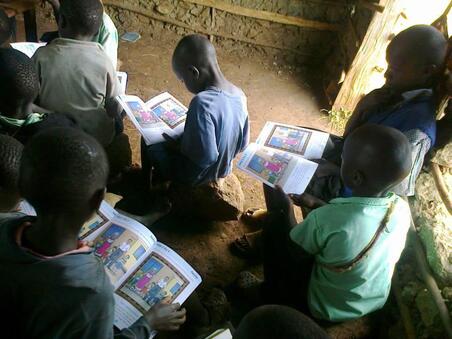

A primary school in Bungoma. Courtesy: Evelyne Jepkemei (on facebook)

A primary school in Bungoma. Courtesy: Evelyne Jepkemei (on facebook) One, is the goof by freshly appointed Education CS George Magoha, speaking with threatening language to teachers opposing the new system, even with promises to crush the system's opponents. Wilfred Sossion, the secretary-general of the teachers' union KNUT, responded in a hard-hitting statement that included arguments about the colonialism and inequality entrenched by the competency based curriculum. Much as Kenyans seem to equate superman tactics of Matiang'i's stint in education with efficiency, even politicians seemed to agree that Magoha's language had gone too far.

The two problems, of parental involvement and inequality, are forms of privatization of education, through shifting the responsibility for education from society to the parent. Once the parent is held responsible for educational outcomes, the government can withdraw its support and blame the deteriorating state of education on the families that are victims of poor educational opportunities. That was the dynamic of the Moynihan report on black families, which held black families responsible for the social impact of flawed public policies, by defining the social problems as a problem with black families. The report entrenched stereotypes of black adults as dyfuntional, which were then mainstreamed to justify the neoliberal policies that reduced public spending on social services.

Focus on the Kenyan family

Just like the prejudice against black people and their educational abilities was brought to Kenya by the colonial government and the missionaries, the ideas driving the Moynihan report, a call to fix black families, were brought to Kenya through the evangelical church. In the 80's and 90's, the mainstream Kenyan TV stations would bring short videos of conservative preacher James Dobson's famous show "Focus on the family" just before the 9 o'clock news bulletin.

Meanwhile, middle class Nairobi Christian families formed groups like Christian Family Fellowship, designed to keep wealth within the same faith circles, and to form relationships between the children that they hoped would end up in marriage or business networks. The pentecostal and evangelical tradition also brought with it seminars for couples and parents, with an increasing number of preachers borrowing from the Dobson model to preach about the nuclear family as the center of society.

Naturally, the racist prejudices embedded in the evangelical American theology infiltrated Kenyan society. Single parent homes - especially led by women - were vilified, and in the place of poverty and poor governance, homosexuality was appointed the number one enemy of families.

The evangelical nuclear familiy narrative has now become so pervasive, that is is now fashionable for Kenyans to click their tongues and blame our social and political problems on the disintegrating Kenyan family. It is now common to hear educated Kenyans say that families are leaving their children to house helps to raise, that they are taking their children to malls where children eat pizza and hamburgers and never learn self-discipline. This narrative has become very difficult to challenge, even when one points out that very few Kenyans can affort pizzas, hamburgers, shopping at malls or to giving pocket money of 10,000 shillings to their children.

And only recently, a citizen expressed concern that private schools were turning away children from families headed by single women. To which Benji Ndolo, a fairly well known Kenyan activist, responded: "Their goal in vetting is to pursue balance, so you don’t have kids coming to school from criminal homes and then undoing all that is imparted to other kids."

In other words, the 3% upper income bracket of Kenyans has become the standard for judging Kenyan society and making public policy. And because most Kenyan families don't meet those standards, all the problems they face - including in educational achievement - are their fault, not the fault of the exclusionary capitalist system.

The tyranny of the 3 per cent

By the time KICD rolled out a curriculum requiring parental involvement, these racist and capitalist imports from the American experience were easy to spot. One of them was the prejudice against black fathers, which was repeated by KICD, thanks to the UNESCO report castigating fathers for not reading their children's report cards.

What is worse is that the policy makers seem unaware of the problems that inequality and prejudice present to Kenyan society. The conversation on Citizen TV, in which I participated (see here and here), was quite frustrating, and raised questions about the information and education that government bureaucrats are exposed to.

The bevy of consultants, bureaucrats and aspiring politicians in the conversation that evening completely avoided the political and moral angles of the debate on inequality. Away from the cameras, from where I was sitting, I could hear my fellow panelists scoff at the questions raised by the parents about the inequalities made glaring by the homework assignments. On camera, though, the KICD Director/CEO Dr. Jwan equated inequality to difference in talent, and essentially said that the country cannot put a program, on hold simply because many Kenyan children cannot participate in it.

One of his statements that showed the government's insensitivity to Kenyans came from in response to a question from anchor Trevor Ambija about what happens to child from Tana River, who, unlike a child from Nairobi, does not have access to a lap top to learn coding. Dr. Jwan answered: "Here we are saying: because we are that different, if the child from Nairobi is doing coding, let us not rank the child from Tana River on the same coding. Maybe there is something else that [the child from Tana River] can do and earn a living. Which is not the case now."

It's one thing for prejudice to be written into policies, and it's yet another for public officials to be so unaware of it. But the most tragic part of this story is that some middle class Kenyan parents have dismissed the ramifications of this parental involvement, thanks to the effective mainstreaming of capitalist, racist and evangelical attitudes towards the family. The most common rebuttal to our concerns has been parents expressing how much fun they are having with their children.

For a continent that has produced Ubuntu - I am because we are - and the proverb made famous by Hilary Clinton, that it takes a village to raise a child, the reaction of these parents is very tragic. It shows an educated Kenya middle class that has weaponized ethnicity to fight each other politically, instead of distilling our cultural wisdom to question what kind of society we are becoming. It shows a middle class completely individualistic and alienated from a social understanding of why we educate, or even of how societies function.

That would explain why there was little outrage at the eat-cake mentality exhibited by the KICD officials in their PR blitz on Monday. At some point, Janet Muthoni Ouko, a member of the CBC task force, even responded to concerns raised about parents working hard to put food on the table with the remark: "parents must create time."

The parental involvement therefore emerges as yet another insidiuous narrative embedded in Kenya's education system, next to the racist idea from the Phelps Stokes commission that sought to alienate Africans from education and training that required their thinking and creativity. And instead of offering a rich curriculum that offers children the ability to be creative, the Kenya government now says that those who are failed by the lack of resources are simply "talented."

It is mindblowing that bureaucrats, scholars and academics can design public policies and systems, with little consciousness of the ramifications. Yet this has been the story since independence. Intellectuals, both Kenyan and international, have been appointed to commissions, and on the basis of poorly conducted or unnamed research, have written life changing policies. These intellectuals have remained anonymous, hiding in government commissions and NGOs, mainstreaming Western ideas into Kenya's governance, while politicians put a public face to sugar coat these policies.

Such practice is undemocratic. We must put intellectuals in a debate over this new education system, so that they too, stop remaining behind university and government corridors and are directly accountable to the Kenyan public for their ideas. As KICD has shown, bureaucrats and intellectuals have become proxies of global interests and racist narratives, and more than half a century after independence, they are importing these narratives into Kenya's education system, .

DEDICATION

I dedicate this post to Binyavanga Wainaina who left us so soon. He knew and spoke about the destructive influence of Kenyan middle class evangelical values, especially through the education system.

Rest in love and revolution, my brother.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed