Source: Cerritos College

Source: Cerritos College It is not surprising, then, that many Kenyans see Matiang’i as the best Education minister we’ve had in recent years. However, his actions are too little and coming from the wrong place.

Sourced from edwinmoindi.blogspot.com

Sourced from edwinmoindi.blogspot.com But the CS and CUE are doing the work of university senates because the control system in-built in the academy has been reduced to almost a skeleton. Ideally, faculty are supposed to be self-regulated through peer review in thesis committees, journal publication and conference presentations, and therefore, they should be able to prevent the reckless increase in university franchises. Moreover, lecturers’ greatest motivation for excellence is supposed to come from interest in the larger social good, which is expressed through academic research and teaching. In other words, if the academy was functioning properly, the university would have robust faculty and well-established senates which would be able to prevent the meltdown that we’re now witnessing in university education.

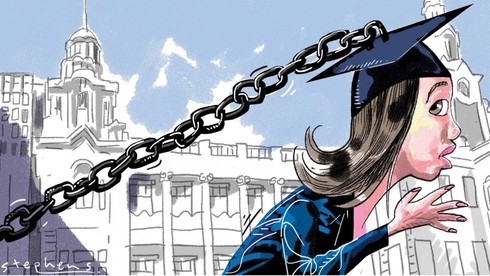

However, any educationist my age and above knows that those kinds of senates no longer exist since their backbone was destroyed by the political elite just after independence. In Kenya, scholars like Prof Anyang’ Nyong’o, Raila Odinga, Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Micere Mugo suffered arrest, detention and exile for teaching and writing about issues affecting Kenyans. The gap left by lecturers in jail or exile was filled by people who cynically toed the line, and whose professorships were awarded more on political loyalty than on academic expertise. And when those professors supervised students, they killed any initiative and creativity, and expected students not to rock any boat.

Later, as the political repression loosened in the 90s, matters were made worse by the neo-liberal economic policies that reduced public funding for higher education. Universities now received less money from government – on orders from the World Bank – but they had to educate many more students. So universities turned to business practices to raise the deficit. With money, rather than academics, as the driving force of universities, university managements grew larger and more powerful than lecturers, and their mandate changed from facilitating education to monitoring use of resources.

Meanwhile, lecturers graduated from having KANU as their sole master; now they also had NGO’s and Western donors willing to pay for lecturers’ souls with consultancies. The neo-liberal economic policies also meant more supervision, and professorships tied to appraisals and to the market value of the programs (huge numbers of students), rather to excellence in academics and teaching. This scenario meant that academics listened more to the market than to their informed opinion, and so would offer little resistance when university managements decided to set up the next franchise, otherwise called a campus.

And as academics let go of their calling, the downward slide in standards in university education became more apparent to the public. The public therefore supported the investment of powers in the defunct Commission of Higher Education (CHE), and now in the Commission for University Education (CUE) to regulate universities. However, the more regulated our university education is, the worse it gets, and the more horror stories we hear.

And the more horror stories we hear, the more we demand regulation. But regulation only makes things worse, because it does not change the fact that profit, rather than education or the public good, is the primary motivation for offering higher education. But motivation for public good cannot be forced down universities’ throats by government; it can only come from the faculty, students, an informed citizenry and progressive political leadership.

Regulation also becomes a stumbling block to, rather than a facilitator of, wholesome education. For instance, while the public complains about outdated university curricula, lecturers’ efforts to create or update programs are slowed down because the Commission of University Education (CUE) subjects programs to lengthy inspection for “quality” and demands extremely high accreditation fees (in the hundreds of thousands). The process is so long and burdensome, that programs get outdated even before they’re taught. Also, university managements demand to recoup the costs of the CUE fees by insisting on full lecture halls.

To manage the inevitable paperwork that comes from regulation, universities have now set up quality assurance offices. That alone, should make everyone shudder, especially when we consider that the original concept is to ensure that each stage of the manufacturing process is done right, so that the customer is satisfied with the final product at the first use. So when that is applied to education, it means we’re educating people for use by others – presumably employers. That means that we’re not educating for the society, for the nation, or most of all, for the individual human being in the classroom.

If we’re educating our young people for consumers and regulators, not for themselves or society, then the students seated in front of teachers are not human beings. And we teachers are under no obligation to give individual attention to the students. After all, the employer – not the student – is the ultimate judge of the value of that student. That realization makes Julius Nyerere’s statement so depressingly real: “no free human being has a market value anywhere. The only human beings who have a market value are slaves.”

Summoning university heads is therefore not enough to repair our broken education system. CS Matiang’i may be a hero in calling university administrators in the wake of public outcry, but what our education needs most is reform from the bottom, not from the top. We need to change the foundations of our education philosophy from the market to the welfare of the nation. We need to restore the love for teaching, restore professionalism and academic freedom. We need professional bodies approved by government – not government – to give accreditation to degree programs. Kenyan academics need to be free enough to offer informed opinions about the state of our nation and of our education systems, and universities should prioritize input from faculty and students, not just from the market, in the decisions they make. As long as academic freedom remains fragile at best, or a dream at worst, Kenyans should expect the downward spiral of our higher education, and, ironically, an increase in government regulation with a bark more noticeable than its bite.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed