Source: http://www.educatorstechnology.com/

Source: http://www.educatorstechnology.com/

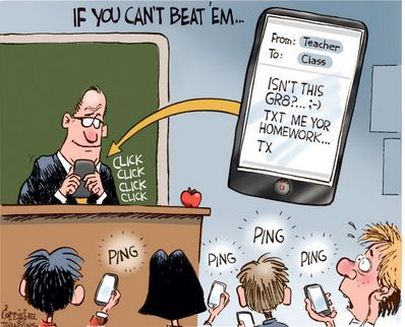

Social media, I was told. Our kids are so tech-savvy, that the sure way to get to them is online.

So within a few weeks, I asked my teenage niece to help me open a facebook account for our department. Yes. I opened a facebook account for our department before I opened one for myself.

But social media did not deliver the promise I hear at every forum praising our kids’ familiarity with technology. As semesters went on, students still said they did not know that our department or our programs existed. I eventually discovered that the real problem was that most students don’t use social media for official purposes like work or education. So no matter how much information we posted on our pages, the students did not see it. I was finally told that the only people they follow are celebs, our department doesn’t feature among the people the students follow, since their teachers cannot be celebs, .

This contradiction continued to perplex me when I would encourage my students to write their research papers on social media. Their grasp of twitter, sorry to say, was not as good as mine. In one theory class, in which my students required a broad view of the world and of current events, I found that some of the students were not even on twitter. I then made having a twitter handle and following certain news personalities compulsory.

Just a few weeks ago, I was telling my students about how the news of Westgate terror attack broke out on twitter, and what I saw were blank faces. So I asked: do you not follow discussions of current affairs on social media? No, I was told. We follow celebs and our friends.

I told the students of that class that since they are not living with their parents any more, they better follow some credible media houses and journalists for their own safety, because it may be good to know any breaking developments.

So in my experience, the only young people whose tech-savvyness I admire are found at iHub, BAKE and computer science programs. To many others, including media students, I have taught how to schedule posts, how to use HTML coding for websites, how to design blogs, how to download articles and books from academic databases, and how to create folders on their emails to classify the research material they find. And every time I show these skills to students, I feel like a fish out of water because, according to the dominant tech narrative, I’m supposed to be the ignorant one, and the students are supposed to be teaching me.

When it comes to technology, I have been looking over my shoulder because this narrative of “now the youth know everything and their teachers know nothing” has dominated the educational technology scene for the last few years. The latest installment of this narrative showed up in yesterday’s Daily Nation, apparently in celebration of the arrival of laptops set for distribution to over one million Kenyan standard one pupils.

This one, published in the Daily Nation, one again portrays teachers as archaic, anti-progress, and most of all, as scared of students taking over their careers and of looking less knowledgeable than their pupils.

The theory behind teacher-dinosaur argument is that there is a time difference between we, the “digital immigrants,” and our youth who are “digital natives.” The difference, the writer explains, is that the current generation of primary school kids was born in the technology era, unlike my generation and older whom computers found already in the world.

This historical perspective is worrying. First of all, a quick glance at Wikipedia tells us that computers have been in the world for over a century. To say that my generation, which has been in the world for less than half that time, was born in an era without computers, is technically not true. The fact that I may not have had contact with a computer in my childhood does not mean that computers did not impact my life at all. They were already being used in war, colonialism and manufacturing. One does not need to have had access to a computer to have been impacted by them.

And for a continent that is yet to overcome the damaging effects of that Hegelian concept of Africa being outside history, we Africans should be wary of tying our presence in this world to our access to a man-made object.

And the theory that being young automatically makes one more tech savvy is a worrying statement to make, especially when it comes to education. The fact that students may be comfortable with technology doesn’t mean that they know how to use it beneficially. As my experience with the students shows, most of our youth, if left to their own devices, use technology for accessing games, gossip, chat with their friends, and even, unfortunately, plagiarism, porn and cyber bulling. Technology has not changed the role of the teacher at all, because the teacher’s job remains to guide (not dictate to) students in navigating the world, even if that world is in cyber space.

Another absurdity in the “DigiSchool” theory is the celebration of multi-tasking. The author writes that our kids are so good at multi-tasking that they can do their homework while watching TV and listening to music on their phone.

I don’t believe that any parent would accept that their children watching TV and playing video games are also doing their homework.

But more than that, if it is true that kids can multi-task that well, why then do schools ban students bringing mobile phones? Why have we not opposed laws against drivers using mobile phone at the wheel, arguing that our young drivers are so tech savvy that they can chat and drive at the same time? Why do several offices have notices asking customers not to answer calls at the counter? And why, oh why, did the immediate former CS for education love to say that kids can only write in xaxa language because they spend all their time texting on their phones?

How many times have we heard people blame indiscipline on parents who leave raising their children to the internet and TV?

When the public wants to dump social and institutional responsibility for education on parents, suddenly the internet and TV are bad and parents are irresponsible, and we call upon adults (especially rich ones) to be sufficiently philanthropic to mentor children. But all that vitriol against technology disappears when the public wants to badmouth teachers as incompetent and to propose technology as the end-all solutions to any challenge in education. In other words, adult input in children’s lives is important and technology is the bad guy only when the public and political leaders want to avoid responsibility for the structural causes of student indiscipline. But when it comes to technology in the classroom, suddenly gadgets in the hands of children become good and they turn children into teachers of adults.

Why this constant shift in the ed-tech narrative?

It's all about the money

Source: Classic 105

Source: Classic 105 But that also goes to show that ed-tech is not the digital equivalent of the teacher. It is the digital equivalent of the text book. If textbooks can’t teach children, neither can laptops.

But even politically, we know that the school laptop project is not at all innocent. When the Jubilee government on the campaign trail made the laptop project part of its manifesto, few Kenyans outside Jubilee supporters took that promise seriously. Within weeks of Jubilee coming into power, Microsoft was making a visit to State House, and the next many months had parliament embroiled in a struggle over the huge sums of money at stake. Eventually, labor leaders of KNUT also added their voice to the money conversation, saying that the money set aside was proof that the government had resources to pay the teachers, only that it didn't want to.

But besides the money which, given our track record with corruption, is definitely lining enough pockets, the laptop project is a campaign promise which few Kenyans have the critical thinking skills to question. That is because laptop is even more difficult to resist than the wads of notes in the hands of Kenyan voters, since it is tangible proof of Jubilee government in the hands of children. Something one can touch always works better than broad intangible promises of better social services.

So I get it: the Jubilee government is gloating over laptops for over one million Kenyan standard one pupils and dismissing those, especially in the education sector, who raise questions about whether the project was what the education system needed. In this winner-take-all country that is Kenya, the message of the laptop project isn’t that the president cares about education, but that he can do what he thinks is best for education and the rest of us can go to he…..heaven. I hate it, but I get it.

But what I cannot get, or even accept, is the argument Kenyan teachers are not professional enough to ask about the EDUCATIONAL value of decisions made about technology, often without consulting them. None of the actors pushing for the purchase of ed-techology can be said to be objective, yet the public rarely gets to hear rebuttals from us teachers when these companies call us dinosaurs because we raise questions.

Ed-technology is not a panacea to all problems pertaining to education. And if my experience is anything to go by, technology actually doubles, rather than reduces, the time we teachers spend preparing for class and teaching. Ed-tech cannot replace the need to professionalize teaching and pay teachers better. It is not an automatic substitute for reforming the curriculum to teach creativity and critical thinking. And nobody, not even children, turns into a knowledgeable expert just because they have a tablet in their hand. That romanticism is for advertising; it does not belong to sober discussions on the future of our children and on the responsibility of adults in helping them get there.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed