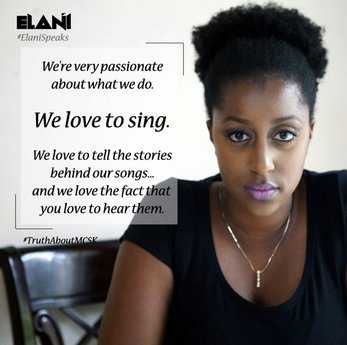

Source: @Elanimuziki

Source: @Elanimuziki Music is human creativity in its purest form. It has no language or ethnicity. Music speaks to our souls even when we don’t understand the words. It reaches far beyond itself. It unites us when we’re divided. It calms us when we troubled. For many of us who study the world and are awed by the good in it, but still have to confront the human capacity for evil, music is the place where we accept those contradictions. Music also trains our minds to be disciplined, warms our bodies by inspiring us to dance, and trains us to be skilled. It is no mistake that Thomas Südhof, 2013 winner of the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, said that he owed his career in science to his basoon teacher.

And music can also put food on the table.

Source: @Elanimuziki

Source: @Elanimuziki For me who has fought tooth and nail to keep our music programs alive at our university, the discussion #ElaniSpeaks presents a single moment that reveals the contradictions within not only the music industry in Kenya, but within our national psyche as well. And these contradictions have deeply impacted music education.

First of all, one of the biggest obstacles our department fights every day is the attitude that music can’t put food on the table. However, the revenues collected by MCSK prove anything but, because the music body rakes in billions from music played in matatus, media, film, adverts and other forums, but returns laughable sums to the musicians. Not surprisingly, some cynical Kenyans are saying that the theft proves that music isn’t a viable career, but we haven’t said the same of agriculture, yet farmers also lose billions in foreign exchange to brokers, auctions and taxes.

The courage to speak so poorly of music and the arts is tied to the political climate in which arts and arts education in Kenya struggle to thrive. In 2010, Deputy President William Ruto, then Higher Education minister, threatened to withdraw funding for the arts programs, implying that the arts are irrelevant. To my knowledge, no one has called him to account for that view, but worse, he now co-heads a government with a schizophrenic approach to the arts.

While the Jubilee government has waxed on and on about its support for the youth, many of whom are engaged in the arts, it has done little to secure the youth already engaged in the arts. Just last week, a few days before Elani released their video, the president was promising the youth from Coast province a talent academy. So #ElaniSpeaks raises the question: what is the point of nurturing talent if the graduates of the academy wont earn a living from it?

And we’re not just talking about music. The Football Federation of Kenya, one of Kenya’s most dysfunctional organizations, evokes a lot of pain in many of us because the bulk of the people affected by the corruption within the organization are the youth. Athletics Kenya is not very far from behind, except that the athletes seem to be more organized in demanding accountability from the body. But that war is far from won.

What pains me most in all these contradictions is this: why have we not asked these politicians about the arts, arts education and opportunities for the youth? In 2012 and 2013, the media treated us to elaborate presidential debates and townhall gatherings, where aspiring political representatives met with audiences to discuss the politicians' agendas. Sure, we were promised stadiums and academies, but if Kenyan sports and arts have thrived so far without them, it means those material things are not within our immediate needs. What we need is accountable leaders in football, athletics, music and any other venture, so that the youth earn from their sweat. Yet the media just asked generic questions about “what are you going to do about…”, to which politicians replied with generic, physical solutions that didn’t address the human heart of the problems each of the sectors is dealing with.

The lesson of the #ElaniSpeaks tragedy is this: we Kenyans have to do our politics differently. Now that we’re heading towards an election, we need to organize forums to meet politicians as interest groups. KNUT should call a teachers’ conference where the teachers tell the presidential candidates what they need to do about education, the laptops project, and the professionalization of teaching. Musicians should call the same candidates and put them to task about royalties and copyright. The universities should challenge the candidates to put forward a coherent policy of higher education. The same goes for women, the disabled, the footballers, sportsmen and sportswomen, the workers, the middle class, the slum residents, the farmers, the journalists, the medical workers and any other group that faces peculiar challenges.

The reason we vote ethnically is because we rely on the media and the politicians to bring us together to discuss politics. The media is interested in ratings, even more than engaging the politicians on matters of media freedom, and so their programs tend to talk about everything under the sun. When we’re not relying on media, we’re relying on bumping into politicians at rallies and funerals where politicians will, inevitably, address us as ethnic groups. We can end this reliance on ethno-politics by organizing for politicians to address us as professionals and social groups. That way, we can stop being impressed by talk of money, buildings and infrastructure, when what we need are enabling environments. Talent academies, stadia, NYS, laptops, hospital and school buildings are useless if musicians, sportspeople, artists, medics, teachers and other youth and professionals cannot earn a decent living from the work they do. We the professionals on the ground can determine for ourselves what buildings and infrastructure we need, and ask for them from the politicians.

Just as music unites us as human beings, #ElaniSpeaks provides an opportunity for us to unite as Kenyans, and start to think politically as Kenyans. 2017 need not be a repetition of past elections.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed