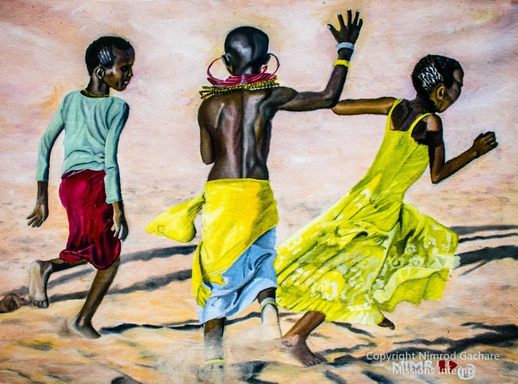

"Worlds apart," Oil on canvas painting 48*35cm by Nimrod Gachare

"Worlds apart," Oil on canvas painting 48*35cm by Nimrod Gachare And yet, Kenyans are willing to give the government the benefit of the doubt. In many cases, even people who are sceptical about the Jubilee government or who have previously raised questions about our education system, have surprisingly joined the “let’s give the government a chance” movement. In worse cases, I was accused of intellectual arrogance and asked why I cannot make a trip to Jogoo house and seek audience with the then CS Fred Matiang’i. The tolerance for the reform has caught me by surprise.

What explains this hostility?

Actually, the reality is more complicated than that. It is probable that the KICD officials were ordered to have this curriculum as soon as possible because it was in the Jubilee manifesto. The president, and his overzealous CS Matiang’i, probably allowed them no leeway to explain that education reform is more complicated than a president snapping his fingers and his CS barking orders. It is likely that even if KICD officials tried, they would have been pointed to former president Moi who changed the education system overnight, never mind the havoc the abrupt change created.

2. People pity the soft-spoken KICD officials as simply doing their work.

This sentiment is completely understandable. If someone is given orders by their boss, they have no choice but to carry them out. Of course, this thinking is problematic because it would mean the KICD officials have no conscience.

3. This is about our children.

Most parents simply want to know that their kids are in school learning things that will be useful for life. No person who loves his or her child knowingly takes their child to a place that will destroy the child. So if someone starts to say there is something wrong with the schools, it is not easy for parents to listen because we're talking about their children. Young people go through this all the time, telling the truth about their schools to adults, and the adults in turn say that the youths have misunderstood the adults' intentions, or worse, that they're spoiled.

4. We have trashed thinking and theory for pragmatism

As Issa Shivji has reminded us, there is a Western vendetta against imagination and theoretization done by African peoples. In the NGO world, Africans are burdened with monitoring and evaluation practices by donors so that the Africans do not take time to reflect on the actions they are taking. In the public spaces, government officials fight against creatives and the malign the arts as irrelevant and a burden on African countries. In education, students are forced to apply Western theories to practical raw data and provide immediate solutions, even when they have poorly misunderstood the problem. The result is that Africa is not investing in long term storage of ideas, which means that every time we’re in a crisis, we adopt solutions that have been crafted elsewhere.

The same is the case for this system change. Kenyans saw for themselves on NTV that KICD has no solid theoretical and philosophical basis for the system. KICD has also repeatedly said that “we cannot keep talking forever, we must act,” yet there is little evidence that the new system was substantively discussed. If anything, the foreign names cited in editions of the Basic Education Curriculum Framework, especially the involvement of the British Council, suggest that there was little local content and knowledge informing this reform.

Done deal

The government presented us with a done deal, a fait accompli, with the expectation that even if Kenyans question the education overhaul, it is too late to reverse the change. I don’t think it is too late to put the new system on hold. But more than that, presenting Kenyans with an irreversible act is an expression of madharau, that is popularly expressed as “uta-do?” Kenyans have to reach a point where we refuse to tolerate done deals, and we say to the government: “we don’t care how far down the road this process has gone. Stop it now, and start it again properly.”

But Kenya has always been a country whose institutional logic is cowardice. In Kenyan institution after Kenyan institution, leaders’ primary goal is to protect their jobs and the status quo, rather than do right by history or by the people. In one rare case, Justice Maraga ordered a repeat of the Kenyan presidential elections, promising to do the same if the repeat was not properly done, but in the end, even he lacked the courage to make the decision again.

So ultimately, our education system will be screwed not just by the president and KICD, but by our unwillingness to order the reform process to be repeated and done properly the next time.

In the meantime, I have prepared some slides for the well-meaning Kenyans who genuinely don’t understand the problem with the education system. Each slide has three sections: a) what the government says about the education system b) what the parents hear, and c) what the reality actually is.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed