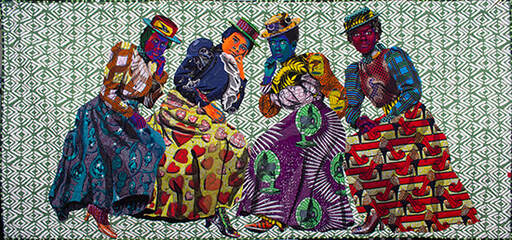

Bisa Butler, ‘I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,’ 2019, Cotton, wool and chiffon, quilted and appliquéd, 50 x 129 in. (127 x 327.6 cm). Private collection.

Bisa Butler, ‘I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,’ 2019, Cotton, wool and chiffon, quilted and appliquéd, 50 x 129 in. (127 x 327.6 cm). Private collection. First was to hear Prof Mugo’s journey of being an African woman in an anti-African world. Recounting her journey was not a story about her, but a story about all of us. From the toxic space that was (and still is) Kenya, to Zimbabwe where she initially landed and finally the United States, Prof Mugo was profoundly African and connected with brothers and sisters wherever she landed. She would later say at a lecture at Riara University, words which I tweeted and may therefore not be verbatim: “If you have chosen the path of struggle, you must have the courage to build a new home wherever your path leads. Don't romanticize home; you must have the courage to make new homes and new roots.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed