A few weeks into the protests that were sparked off by the Kenya government’s belligerent persistence in passing the Finance Bill, the government spokesman, Isaac Maura, held a presser in which he offered a strange apology to Kenyans. As he announced the president’s concessions to the protestors’ demands, he talked off the script and said: “On behalf of any public official who has been seen to be opulent, proud and arrogant, I wish to issue an unreserved apology to the people of Kenya. Going forward, public officials shall demonstrate responsibility and humility, as has been instructed by our appointing authority, our president.” He repeated, “I wish to offer an unreserved apology for that opulence and arrogance of matters that could be seen to be contemptuous of the sufferings of Kenyans.”

0 Comments

A market scene painted by Ugandan painter Hoods Jjuuko. A market scene painted by Ugandan painter Hoods Jjuuko.

I wanted to wait to write about Mwalimu Micere Mugo until the rites to honor her life were completed, because I wanted to respect those who knew her intimately. I didn't. I met Mwalimu only three times, once at Riara University, another time at University of Nairobi, the other time at the memorial of her daughter Njeri Kui. All were public events, so I'm almost sure she barely remembered shaking my hand, or me re-introducing myself or being re-introduced to her, especially when she was grieving her daughter.

So I do not grieve Micere Mugo as I would a close friend. Instead, I grieve her as my mile stone. Since the day I heard her speak in person, almost ten years ago at the University of Nairobi, she has been my intellectual north star. My guiding light. When I heard her weave her ideas with her poetry, and engage the audience in her performance, I knew that that is what I wanted to be; not necessarily an oraturist like her, but an intellectual who weaves humanity into her thought, relations and politics. And then being in literature, many of my colleagues were taught by her and were friends with her. So her influence on me is probably what she aspired for, which is to influence humanity through humanity.  David Livingstone preaching from a wagon. Source: Wikipedia David Livingstone preaching from a wagon. Source: Wikipedia

A child who went to school beginning in the 1970s, like I did, was fed on a steady dose of “the white man stole our African cultures” as a slogan that explained all Kenya’s socio-economic problems. And if one pursued literature as a subject, that slogan was repeated to the point of becoming shrill.

At least that’s how I see it today. Back then, as I child, I treated it as the gospel truth that I carried with me through all my student life, up to my doctoral studies. After all, many of the gurus of decolonial thought are Kenyan, with the classic text on decolonizing the mind being written by a Kenyan. There is no way one could get away – especially not in literature – with not quoting them, without it being thought that we were ungrateful to our elders.

The Kenyans who are really blinded by religion are not the ordinary ones who are actively religious, but the educated ones who are against religion. It’s an intellectual entanglement so spectacular that would put the emotional entanglement of the Smiths to shame.

* When William Ruto won the 2022 general elections to become Kenya’s fifth president, local and international media were awash with discussions of Ruto as an evangelical president. The excitement, however, was informed less by Kenyan religion or politics and more by right-wing Evangelical America and its war on homosexuality and abortion. Le Monde, a major newspaper from a country that boasts of being the home of the Enlightenment, was understandably preoccupied with Kenya’s adherence to secularism. The BBC was curious about the president’s stand on homosexuality, but not about secularism, which would have been strange for the public broadcaster of a country whose head of state is also the head of the Anglican church. We need a national philosophy of education: My submission to the Working Party on Education Reforms6/12/2022

For those interested, you can download the entire document at the link below.

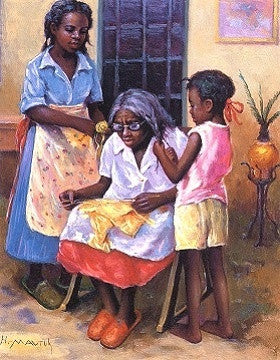

Three Generations, painting by Hulis Mavruk Three Generations, painting by Hulis Mavruk

Many with a decent knowledge of neo-colonialism and global racism may have been shocked at the amount of Western decadence, from Anglo-American political stars and billionaires, that has flowed into Kenya in the first few months of President Ruto’s tenure.

Without a public discussion, the ban on GMOs was lifted by decree, with a fairly racist caveat that since we Kenyans are dying of famine anyway, we need GMO foods to fill the gap. Weeks later, this dystopian logic would be openly articulated by the Trade CS who, in a poor attempt at sarcasm, said in the midst of the morbid laughs of his elite audience: “By just being in this country, you are a candidate for death. And because there are so many things competing to kill you, there is nothing wrong with adding GMOs to that list."  "In the muddy pool," painting by Anthony Mwangi "In the muddy pool," painting by Anthony Mwangi The period immediately following the 9th August general elections in Kenya was a rude awakening for many. In any contest where there’s only one winner, and so there the contrasting feelings of jubilation and disappointment are no surprise. What would shock a keen observer is the visceral negative reaction shock amongst a section of the supporters of the Azimio la Umoja side. The reaction went beyond disappointment; it was grief that quickly deteriorated into recriminations against any individual or group perceived not to have ‘given their all’ in support of Rt. Hon. Raila Odinga’s candidature. This is Mr. Odinga’s fifth stab at the presidency, so the spectre of disappointing results is not totally new to his supporters, particularly those over 40 years old. Disappointment and even certain levels of anger have been de rigueur in past elections, but the inexplicable grief and recriminations have been unique to 2022. One unique feature of this year’s elections is that the narrative has portrayed those perceived not to have supported Raila not as competitors or rivals, but as evil saboteurs. |

|

||||||||